There are 136 inhabited islands in the British Isles, according to Wikipedia. In this post, I shall concentrate on the two biggest: Great Britain and Ireland, country by country.

Republic of Ireland

My first visit to the Republic of Ireland was in 1974 with my first wife-to-be (as she was then). We did a circuit of the south coast and returned for a couple of nights in Dublin at the end of our holiday.

My recollection was that Ireland was a poor country: the buildings were a little shabby and the rural parts were still very socially conservative. The country felt oppressed under the heavy, authoritarian fist of the Catholic Church. I saw the deference with which locals showed to their local priest, a god-like figure in the community. All in all and coming from London, we felt we had stepped back in time about twenty years or more. Dublin had some interesting historic sites and buildings – I particularly remember Trinity College – but was in many ways unremarkable. The Temple Bar area was quiet and semi-derelict, a far cry from the youthful and vibrant quarter of the city much favoured by British (and Irish) hen and stag parties in more recent times.

Two things that struck me have not changed. The first – and most commonly commented upon by visitors – was the friendliness of the people we encountered. The second was the mixing of people of all ages, at a Caleigh, in a pub, to have a good time. (The English, then and now, seem to me to socialise within their own age groups, especially so in London and the South East. It might also be more of a middle-class thing.)

Northern Ireland

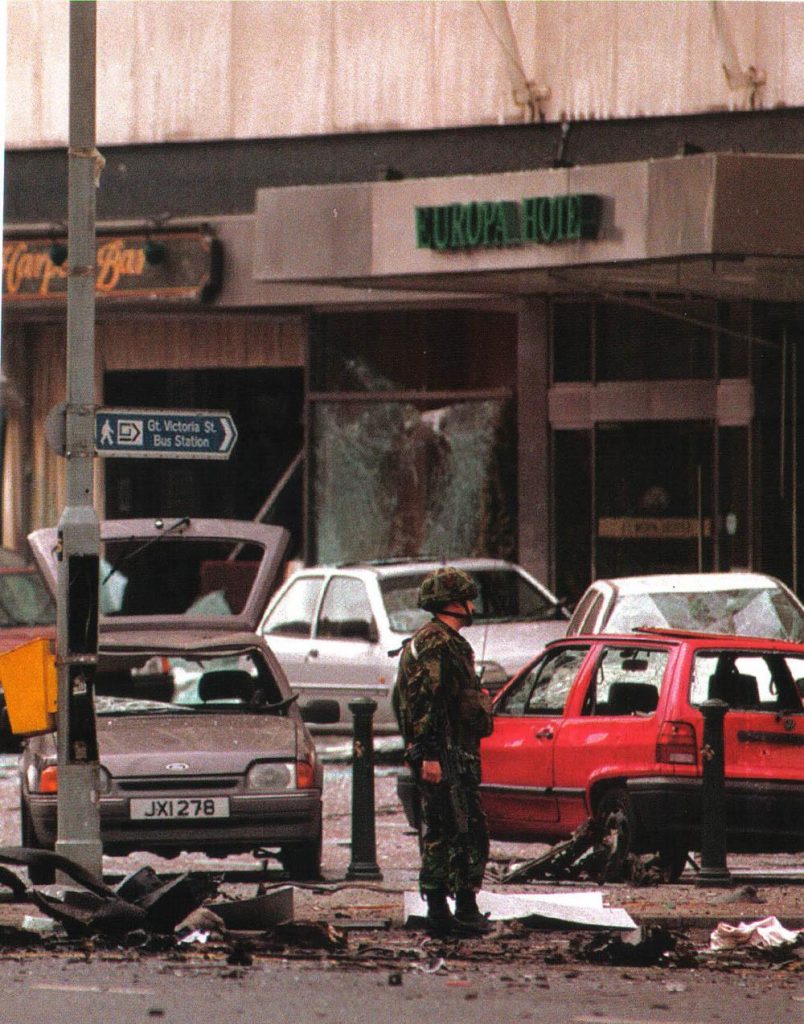

My only visit to the six counties of Northern Ireland was for work, during the so-called “Troubles” in the 1970s. A more honest term might be Civil War. I can’t even remember now what the purpose of my trip was. What I do remember is sitting in the restaurant, alone, at a table beside a very large plate glass window which acted as the outside wall to the street below. I was staying at the Europa Hotel in Belfast, Europe’s most bombed hotel. It was bombed 36 times during this period, according to Wikipedia. I remember thinking “Is this wise?” Happily, nothing untoward happened during my stay, but I do remember the oppressive and unnerving security checks everywhere I went.

The Good Friday Agreement brought peace and reconciliation to the north of Ireland, contingent on the UK and the Irish Republic both being members of the EU. Let’s hope peace continues, despite the stupidity of the current batch of politicians. The DUP are now mad that the UK parliament has voted for equal marriage for same-sex couples and abortion rights for women to bring this corner of the UK into line with the rest of us. Who knows what will happen next?

Scotland

I’ve had several trips to Scotland, occasionally on business, but more often as a tourist. Scotland voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU in the 2016 referendum. Scottish independence is certainly on the cards – I would certainly vote “yes” in the next independence referendum if I were fortunate enough to be Scottish – but I’m not. I have exactly as much say in Scotland’s independence as I do about who will be our next prime Minister: a hostage in my own land.

My wife and I enjoyed our trip to Glasgow last autumn: a vibrant and interesting city. We’ll be travelling to one of the western isles later this year. We can check out the vibes in a beautiful part of our islands.

Scotland’s form of nationalism seems pretty progressive and social attitudes similarly so: much the same applies in Ireland, especially since Sinn Fein modernised its policies and adopted progressive attitudes to women’s rights and same-sex marriage. The English form of nationalism, by contrast, verges on fascism.

Wales

The Welsh are something of an enigma to me. We’ve recently returned from a week’s holiday in Snowdonia, a stunningly beautiful part of these lands. In the 30-35 years since my first visit, I notice an increase in the prominence of – and perhaps pride in – the Welsh language. Recent opinion polls show a clear lead for Remain, in contrast to the 2016 result in Wales. Perhaps the message about all that European Regional Development Fund money is finally breaking through there.

England

Which just leaves the fucking English – of which I am one. Ah… England, land of inequality and lack of opportunity for most. The near certainty of yet another old Etonian as Prime Minister. The near certainty that he will be the third person in a row to earn the distinction “Worst PM in my lifetime”. What on earth is the matter with us?

A small consolation prize: the thug Stephen Yaxley-Lennon is in jail. Good! What’s this? His 12th criminal conviction, I think.

England v Ireland

All of this leaves me to ponder on one thought: the contrast between England and Ireland over the last 30-40 years. During this time, Ireland has progressed beyond all recognition: from a backward, relatively poor theocracy to a modern, inclusive forward-looking democracy. (Not perfect, by any means, but stupendous progress has been made in a relatively short time.)

England, by contrast, seems to be regressing into a divided, hateful, intolerant and bigoted place. Honourable exceptions are the cities: London, Cambridge and Oxford spring to mind – prompting accusations of elitism from me, of course. Sadiq Khan seems a breath of fresh air as Mayor of London after the embarrassment of his predecessor and his ludicrous vanity projects.

So why is there such a contrast between Ireland’s and England’s progress to modernity over the past three to four decades? Both countries joined the EU (EEC then) in the same year, 1973. I struggle to provide a convincing explanation.

Nostalgia and English Exceptionalism

A partial explanation lies in the phenomenon known as “English exceptionalism”. This seems to have been explicitly recognised and discussed only in the past few years – and especially as one of the explainers for the denialism and fantasies of many Leave supporters. A much longer-standing problem has been the whitewashing of our imperial past. It is only in the last decade or two that our education system has started to take a more critical and impartial view of the history of the British Empire. This means that anyone over the age of about forty was told by the state (i.e. at school) a wholly one-sided version of the imperial story.

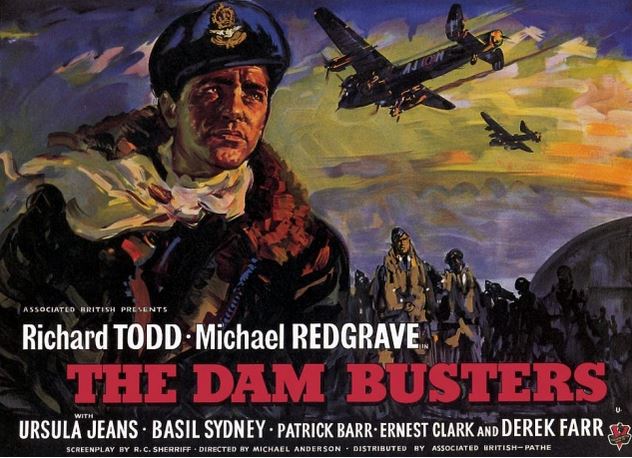

The mix is made more toxic by a strange nostalgia for the second World War and “plucky Britain’s” survival of the blitz. Historian David Olugosa, writing in today’s Observer, makes an interesting, and much overlooked, point. Those old enough to have actually been alive during WWII and who saw the suffering first-hand, were “far more likely to oppose Brexit” than baby-boomers. (More details are available at this LSE British Politics and Policy blog post.) Olugosa describes my generation as “brought up watching war films rather than cowering in Anderson shelters”. One of my schooldays memories is that the climax of the school’s Film Club season one year was a showing of the film Dambusters – all stiff upper lips, bouncing bombs and militaristic music.

It seems that, unfortunately for those of us who voted remain, that 2016 was exactly the worst time to hold a simplistic “in/out” EU referendum. Yet this still does not fully explain why the English of a certain age are uniquely prone to this stuff. The Republic of Ireland, of course, was officially neutral during the war: does this sufficiently explain the difference? Or is it somehow bound up the English class system? Any ideas?